by Paul Kreingold, Leesburg, VA

December 19, 2019

Introduction

The destruction of Washington D.C. in August, 1814 by the invading British challenged President Monroe and Benjamin Latrobe with the task of rebuilding the edifices which had been destroyed. As did Washington and Jefferson earlier, they understood that the principal buildings of the government were not mere offices but symbols of the aspirations of the Republic. They had to be more than functional, they had to be beautiful. As classicists, their notions of beauty were derived from the ancient Greek and Roman Republics. Like the Greeks and Romans, the preferred building material was marble. The question was, where was such building material to be found?

In a report to the Committee on Public Buildings on November 28th, 1816, Benjamin Latrobe describes a stone which is a “very hard but beautiful marble” which “has been proved to answer every expectation that was formed, not only of its beauty, but of its capacity to furnish columns of any length, and to be applicable to any purpose to which colored marble can be applied.“ Latrobe continues, “The quarries are situated in Loudoun county, Virginia and Montgomery county, Maryland.”(1)

Latrobe is describing Potomac Marble which is a ubiquitous limestone conglomerate whose deposits stretch from south of Leesburg, Virginia to the shores of the Potomac River in Montgomery County, Maryland. It is not actually marble, which is metamorphosized limestone, but a sedimentary conglomerate consisting of pebbles of various sizes and composition (clasts) held together by a limestone (calcium carbonate) matrix. Ultimately, Potomac Marble was used by Latrobe for the columns in the Capitol’s old House and Senate Chamber. The unique characteristic of this marble is its color described here by Latrobe: “as the Cement which unites the pebbles does not receive quite so high a polish as the pebbles themselves, the Mass acquires a spangled appearance, which adds greatly to the brilliancy of its effect.”(2) Visitors to the old Senate and House Chamber (Statuary) can still wonder at the beauty of these columns now two-hundred years old.

Latrobe is describing Potomac Marble which is a ubiquitous limestone conglomerate whose deposits stretch from south of Leesburg, Virginia to the shores of the Potomac River in Montgomery County, Maryland. It is not actually marble, which is metamorphosized limestone, but a sedimentary conglomerate consisting of pebbles of various sizes and composition (clasts) held together by a limestone (calcium carbonate) matrix. Ultimately, Potomac Marble was used by Latrobe for the columns in the Capitol’s old House and Senate Chamber. The unique characteristic of this marble is its color described here by Latrobe: “as the Cement which unites the pebbles does not receive quite so high a polish as the pebbles themselves, the Mass acquires a spangled appearance, which adds greatly to the brilliancy of its effect.”(2) Visitors to the old Senate and House Chamber (Statuary) can still wonder at the beauty of these columns now two-hundred years old.

In Loudoun County, Virginia and Montgomery County, Maryland

The investigator who desires to search for the remains of the Potomac Marble quarries “in Loudoun county, Virginia and Montgomery county, Maryland” will find himself quite frustrated as the specific locations are never revealed by either contemporaries or those that write about them. The mystery starts quite early. For example, Samuel Lane, the Commissioner of Public Buildings lists a disbursement dated May 21, 1816 for $16.00 for “Hack hire to marble quarries” and another paid to Latrobe for $161.27 for “Expenses exploring marble quarries.” (3) Which marble quarries? Who owns them? Where are they?

Latrobe’s biographer Talbot Hamlin in his six-hundred-page work makes no attempt to identify quarry locations and only repeats a story told by Latrobe’s son about the discovery of the marble on the Loudoun estate of Samuel Clapton. He implies that the quarries were on this estate but there is no other proof of this and much of the rest of the story is apocryphal. (4)

Other historians write that the marble came from the “banks of the Potomac River, just above Conrad’s Ferry”;(5) “both sides of the Potomac River in Loudoun County, Virginia and Montgomery County Maryland”;(6) and “in Loudoun County Virginia.”(7)

Cartographers are not any clearer. For example, a much-quoted early Loudoun cartographer, Yardley Taylor while discussing Potomac Marble in his 1858 Memoir of Loudoun County says, “This rock was used for the pillars in the Capitol at Washington, and may be seen in the Representatives Hall and Senate Chamber.”(8) Mr. Taylor never identifies a Loudoun quarry location even on his 1853 map which is the first detailed map of Loudoun County and can be seen at the Balch Library in Leesburg.

Geologists are no exception. The 1898 Maryland Geological Survey reports, “There is some doubt as to the exact location of the particular source of these blocks used in the capitol.” (9) Joseph K. Roberts writes in his 1928 book, the Geology of the Triassic:

“The rock was first noted by B.H. Latrobe who selected it for columns in the National capitol. It would seem from Latrobe’s account that the quarries from which the stone was taken were located in Loudoun County, Virginia and in Montgomery County, Maryland.”(10)

There is that phrase again!

Loudoun historian and mapmaker Eugene Scheel suggests two locations in Loudoun which may have been sources of Potomac Marble for Latrobe. These are Olde Izaak Walton Park and the Leesburg Limestone Quarry both in the town limits of Leesburg.(11) These are real possibilities but require more investigation. It should be noted that Scheel identifies the pond at Olde Izaak Walton Park as the filled in quarry. I have mapped the depth of that pond and nowhere is it more than seven feet deep. Additionally, I have photographs from 1955 of Izaak Walton members digging that pond. (12) The actual quarry in that park is about 200 yards south of the pond hidden by trees and poison ivy.

Government publications do not provide much more help. In a pamphlet published in 1975 by the U.S. Department of Interior, Building Stones of Our Nation’s Capital, it is written: “Until the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was finished, the huge blocks were brought overland from quarries near Point of Rocks, Maryland, 46 miles west of Washington.”(13) Interestingly, when that pamphlet was re-published in 1998 it was ten pages smaller and only says that Potomac Marble came from “various localities.”(14)

There is, on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal towpath a Marble Quarry Campsite at milepost 38.2. On the C&O Canal Trust web page it is described as follows:

“According to old maps, before the C&O Canal was built, there was a ‘Marble Quarry’ running along the Maryland side of the river for over a mile. The stone that was quarried here was known as ‘Potomac marble,’ which wasn’t a solid substance, but rather was composed of angular pebbles held together by a limestone matrix. Benjamin Latrobe discovered Potomac Marble with its varied and rich colors and made the decision to include it in the Capitol buildings he was designing. (15)”

I have found no evidence of a quarry near this campsite.

This leads us to ask, “Doesn’t there exist at least one two-hundred-year-old hole-in-the-ground which we can prove was a source of the Potomac Marble for the columns in the Capitol?” Now, at last, we can answer, “Yes, there is!” It is located 2.2 miles upriver from White’s Ferry on the C&O Canal towpath, at milepost 38. Its coordinates are 39.177192, -77.4960702.

The Investigation

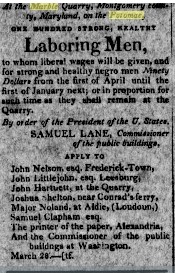

In the April 8th, 1817 issue of the Genius of Liberty, a local Leesburg, Virginia paper there is an advertisement which reads:(16)